In case you haven't read the Chicago Tribune yet today, we wanted to pass along this article! Today starts National Infrastructure Week 2016. This year's theme is "Infrastructure Matters” and works to tell the story of what infrastructure means to Americans. Of course, the RTA region's public transportation system is part of that infrastructure.

The big sell: Making people care about infrastructure repair

Mary Wisniewski Contact Reporter Getting Around

In comic book movies, transportation infrastructure problems are easy to spot.

Bridges fall. Asphalt shatters. And unless Ironman funds the repairs out of his personal fortune, big public debt issues are ahead.

In real life, damage to roads and rails tends to be gradual, though ultimately just as ruinous to regional well-being.

With a new Illinois

capital program delayed as the state goes 11 months without a budget, transit leaders have been sounding the alarm in both Washington, D.C., and Springfield about the dangers of waiting too long to invest in infrastructure. Business, labor and transit leaders will ramp up discussion nationwide Monday for the start of the thrillingly named Infrastructure Week.

It's a tough sell — roads, buses and trains seem to work just fine until they don't, and politicians don't like to raise gas taxes or other user fees. Regional Transportation Authority Executive Director Leanne Redden admits that funding for bridges, signals and tunnels is not a sexy topic, but it's crucial to keep the system going the way it should.

"The system is safe, but the system is starting to lose on reliability, and you end up spending more money trying to maintain an old system," Redden said. "I don't want to squander the great system we have."

The Metropolitan Planning Council, which consulted with RTA officials and other experts around Illinois, determined that meeting the state's transportation deficit requires an additional $43 billion over 10 years — on top of what is already expected in terms of capital funding.

The longer the wait for capital dollars, the bigger the problems will get in terms of cars damaged by potholes in the road, lost hours due to traffic and transit delays, with a growing chance of catastrophe like the recent all-day Metro shutdown seen in D.C., said Joseph Szabo, executive director of the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, which oversees land use and transportation planning for the region.

"It really is time to start ringing the bell because we're reaching a point where it can soon be a crisis if we don't address it," Szabo said. "This has a direct impact on quality of life, on the ability to move goods, on people's ability to get to work."

A regional problem

Every local transportation agency has a story of delayed projects and potential missed chances because of a lack of capital investment.

For the

Chicago Transit Authority, for example, the lack of state capital funding has meant $1 billion in federal money may get left on the table. The passage of the Fixing America's Surface Transportation Act last year made federal dollars available, but state matches are needed to access them.

"A capital program would be very helpful, or else those funds could be put at risk," CTA President

Dorval Carter Jr. said. He said the money is needed for projects like the Red and Purple Line modernization, and rail and right of way improvements to prevent slow zones.

CTA needs a total of $13 billion in capital spending over the next decade to get the system in a state of good repair, Carter said.

Metra needs $11.7 billion in capital funding over the next 10 years. Because that's a tall order, the board has made two programs top priorities — positive train control, a federally mandated computerized system to prevent train collisions, and new or rehabbed rolling stock. That would include 367 new railcars. (The agency currently has funding for 10.)

Some of Metra's railcars are 63 years old. "They're eligible for Medicare in a couple of years," joked Metra CEO

Don Orseno ruefully.

Besides new cars and locomotives, Orseno said Metra needs a better maintenance schedule for its old ones. Walking around a big, barnlike rail repair facility on 49th Street last week, Orseno and Metra capital projects manager Lexie Walker showed how cars are stripped down and rebuilt — with new floors, seats, toilets, air conditioning, outlets for plugging in laptops and wheelchairs, plus new wheels and brakes.

But the 70-year-old facility only can do about 30 cars a year — Orseno would like to spend $20 million to modernize it so cars can get in more frequently. Some cars wait 20 years for rebuilding when they should get an overhaul every 12 to 14 years, Orseno said.

Without reliable rolling stock, delays will increase on a system that carries 300,000 riders a day. Without Metra, Orseno noted, the state would need to build an extra 29 lanes of highways.

This is unlikely, since the state cannot afford to keep up the roads it has now. One of the pressing needs for the

Illinois Department of Transportation is a rebuild of the aging and congested Eisenhower Expressway, similar to the reconstruction of the Dan Ryan in 2007, said Peter Skosey, executive vice president of the Metropolitan Planning Council, a nonprofit focused on regional growth.

"Money for that project isn't even on the radar," Skosey said.

He noted that no system is going to be in perfect shape all the time — it's like your house, you want to keep it in a state of at least 90 percent repair, with a few projects on a to-do list. But Illinois' state of repair is currently below 80 percent and could drop below 60 percent in the next five years, Skosey said.

Skosey noted that closed roads and bridges lead to gridlock, which already costs the region $7 billion a year. On an individual level, bad roads cost the average Illinois driver $400 to $800 a year in car repairs.

Paying the bill

The planning council figures that additional capital funding can be paid for through a 30-cent hike in the gas tax and a 50 percent hike in registration fees.

This would be tough — there hasn't been an increase in the 19-cent Illinois gas tax since 1991, or in the 18.4-cent federal tax since 1993. Illinois registration fees bumped up three years ago.

Another way of getting funding is through congestion pricing. Gov. Bruce Rauner has proposed creating toll lanes as part of the modernization of the Stevenson Expressway.

Some type of "vehicle miles traveled" or VMT tax, which would charge drivers for use of the roads, is another possibility. This could be charged through a flat fee, which assumes that everyone drives a certain amount a year, or through a GPS-type device that accurately measures each car's miles.

The advantage of VMT over a gas tax is that as cars get more energy-efficient, a gas tax will be a less reliable way to get revenue. But there are obvious kinks in a VMT system, since a flat fee would benefit frequent drivers and be a disadvantage to those who don't drive as much. And a GPS-device would raise privacy issues.

Skosey sees VMT as the right approach, but not for five or 10 more years.

Illinois is certainly not the only state with infrastructure funding problems. The American Society of Civil Engineers has given the nation's infrastructure a "D+" grade and figures that in the next decade, every U.S. household will lose $3,400 annually because of infrastructure deficiencies.

But unlike Illinois, about 16 states have managed to raise their gas taxes in recent years, including conservative, tax-shy Nebraska and Idaho.

One sign of hope is a proposed constitutional amendment on the November ballot that would guarantee that levies such as the gas tax, tolls and license fees would be put into what amounts to a budget "lockbox" for transportation, Skosey said.

He said he thinks this would give the public greater confidence to support additional user fees — if they know the money is going to patch roads and not other Illinois' other budget holes.

"They understand the need," Szabo said of Illinois voters. "They're the ones that are stuck in traffic."

mwisniewski@tribpub.com

RTA celebrates 30 years of the Americans with Disabilities Act

RTA celebrates 30 years of the Americans with Disabilities Act

Take a survey to help improve mobility options for older adults and people with disabilities

Take a survey to help improve mobility options for older adults and people with disabilities

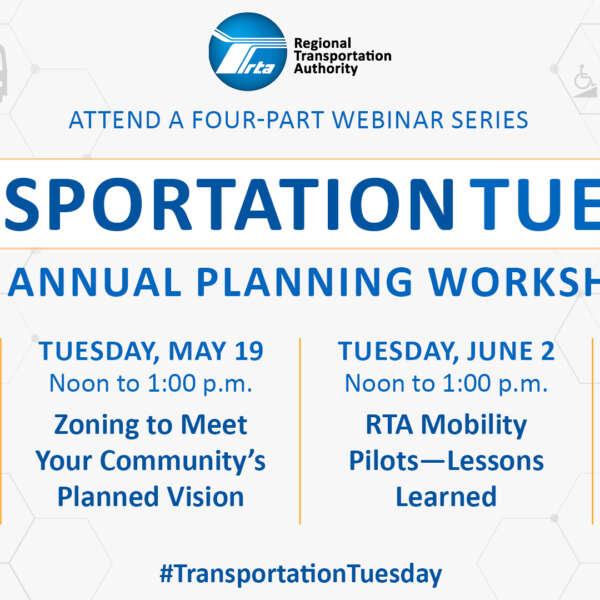

Transportation Tuesday Webinar Series: Attend the 2020 RTA Annual Planning Workshop Virtually

Transportation Tuesday Webinar Series: Attend the 2020 RTA Annual Planning Workshop Virtually

Announcing the 2020 Access to Transit Program Call for Projects for Small-Scale Capital Projects

Announcing the 2020 Access to Transit Program Call for Projects for Small-Scale Capital Projects

Happy International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month from the RTA

Happy International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month from the RTA

How's Your Ride? Take This Survey

How's Your Ride? Take This Survey